Press Start to Compose

What started out as a half-hearted attempt to give my studio “a bit of an arcade theme” spiralled further out of control last year, leaving me with what I can only describe as an “arcade with a bit of a music studio theme”.

I lay the blame for my cavalier attitude towards arcade machine acquisition squarely at the feet of my inner twelve-year-old, a socially awkward and troubled boy trapped somewhere in 1983.

And if this already points towards some sort of midlife crisis – which it probably does – then I feel I can at least console myself with the idea that it’s a fairly cool manifestation of one.

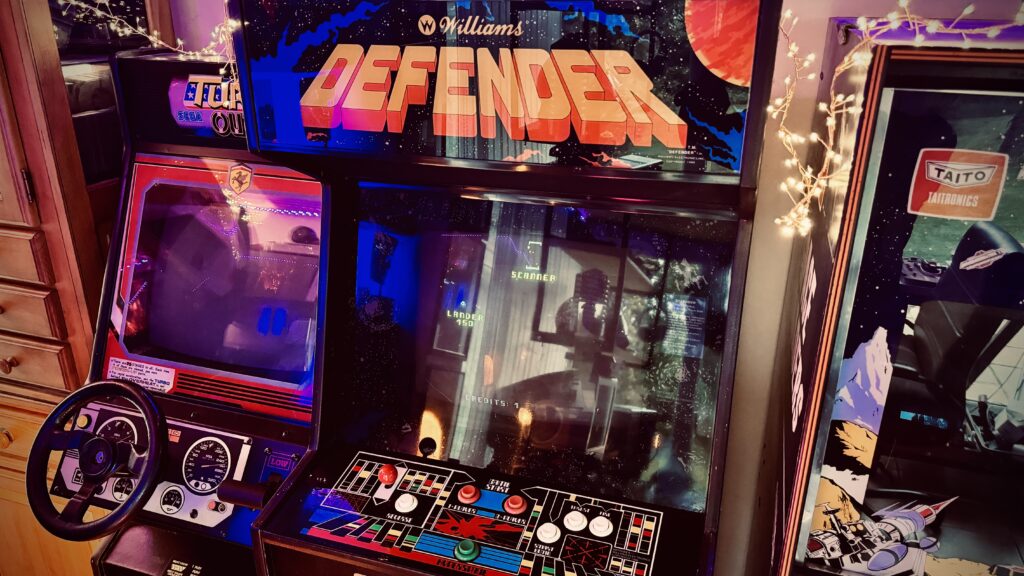

For some, it’s sports cars and marathon running. For me, it just happened to be garish multi-coloured lighting and games such as Defender and Space Invaders.

Inner child James declared war on his adult self earlier this year, with arcade machines becoming the chosen battleground. Across the decades, young James had screamed at outer adult James to play Atari Star Wars again – believing, naively, that this may transport him back to Bournemouth’s magnificent Pier Amusements during the 1980s.

Child James wasn’t wrong: Playing Star Wars again – thanks to the emergence of a fairly decent ‘replica’ from Arcade 1UP – proved to be a pretty thrilling experience. The familiar yolk, the assault on the Death Star, the glowing vector graphics (albeit rendered on an LCD rather than a CRT monitor), the emulated POKEY chip music and a grainy sampled Sir Alec Guinness are much as big James remembers them.

I’m tempted to crack a joke here, describing this kind of midlife-crisis as something of a quarter-life crisis, but for a British person accustomed to pumping ten-pence pieces into coin slots instead, that would be inexcusable. (Too late, it would seem).

There’s no doubting that much arcade paraphernalia – and the culture surrounding it – originated in the US and Japan, even if the British have long had their own unique way of celebrating it – particularly, as I recall, in and around seaside resorts.

I read a wonderful book by Alan Meades on this subject recently, called Arcade Britannia: A Social History of the British Amusement Arcade, which I can wholeheartedly recommend.

VINTAGE OR REPLICA?

At the risk of becoming overly techie on what is supposed to be a composer’s website, I’ll quickly answer this question by saying that I enjoy both vintage and replica arcade machines (and any retro “re-issue” consoles, for that matter).

The ongoing war with my younger self has only intensified in recent years, brought on by the frustrating availability of newer, fully-licensed ‘replicas’ from the likes of Arcade 1Up and AtGames. These cabinets – although lacking CRT monitors and being flimsier than the vintage arcade machines they seek to emulate —are appealing for the casual arcade fan and, unlike some other solutions, don’t rely on the acquisition of illicit ROMs in order to work. I’ve had a few of these cabinets imported from the US, and do enjoy them. Brought together in a dimly lit room, side by side with the real thing, they do successfully manage to create a welcoming arcade vibe. They sound the part, too, producing the kind of unmistakable arcade soundscape (some might say, cacophony) I fondly remember from my youth.

Deemed inauthentic by aficionados and arcade purists – understandably – I wonder if some of these newer replicas (and I do use that word loosely) will themselves end up collectible some day, much in the way the many cheap, plastic tabletop games of the 1980s (such as the likes of Grandstand’s Astro Wars) have done since they hit the scene.

As a kid, I can well remember purists scoffing at those, too. Yet, now, these little devices are considered ‘vintage’ collectibles. (Or should that be ‘retro’ collectibles? – I’ve never really been clear as to the exact meaning of this word. Does it mean old or something more akin to new old – i.e. styled after older products?). ‘Vintage’ – I think – means actually old.

Given enough time, it seems as though almost anything powered by electricity – toasters included – will eventually acquire a degree of retro tech charm, serving as a reminder of just how subjective and, dare I say it, age-related this hobby can be. Innovation and quality do motivate part of the interest, of course, but nostalgia, cultural impact during one’s formative years, generational influences and so on, do appear to play a fundamental role as well.

WHERE ARE ALL THE ARCADE MACHINES?

Much old tech end up in landfill, and it seems that in previous decades many ancient arcade machines have sadly met the same fate. Were that not the case, there would surely be many more of them in circulation, especially given how many of the things used to exist.

I’ve heard it said that, after various arcade machines fell out of fashion and became commercially unviable to arcade owners during the late 1980s, some of them proved difficult to even give away. Many were thrown out, burned, or even dropped into the sea (really).

How deranged would someone need to be to drown an arcade machine?

Many arcade machines simply fell into disrepair, with some now so old that sourcing the custom-made replacement parts needed for fix them has become extremely challenging. The ongoing maintenance of CRT monitors in particular appears to be a significant issue, as they are scarcely manufactured today and few people appear to possess the skills required to repair them.

WHAT – OR WHEN – IS RETRO?

This is a difficult question, and one I don’t feel qualified to answer, but according to the podcast, This Week in Retro – of which I am a keen listener – “retro” (in gaming, at least) is defined as anything released up to and including the Playstation 3 console.

That’s for now, anyway, as the goalposts are always moving.

Off-topic a little, I was surprised to learn recently that even some of games I’ve worked on during the earlier part of my career are now considered vintage by some, which I find surprising and terrifying in equal measure. Some of the people who occasionally write to me with questions about now apparently old games such as Theme Park World, Privateer: The Darkening, Flight of the Amazon Queen, Freelancer, Space Hulk, Evil Genius, Conquest, Grand Prix 4, Cutthroat Island, Shadow of the Horned Rat, Art Academy and a bunch of others mostly from the 1990s or early 2000s (and even some EA Sports titles and games such as Red Alert 3 – which I flat-out refuse to believe are actually “old”) are usually way younger than me – often growing up during the era in question. This, I think, says a lot about the nebulous definition of ‘retro’.

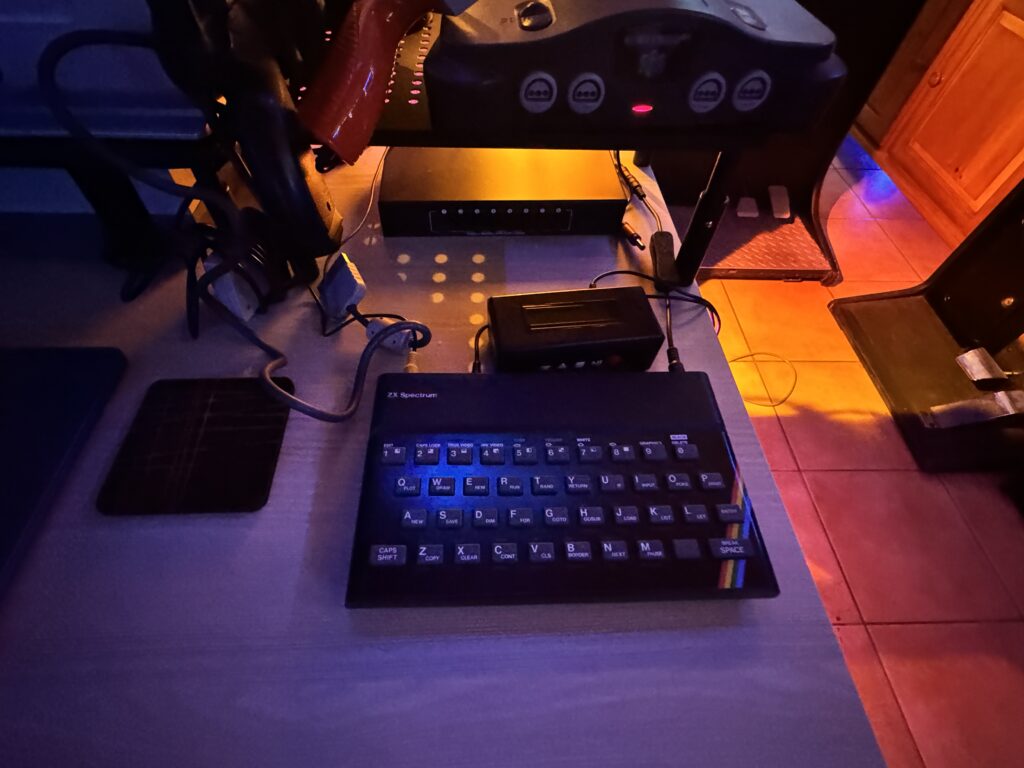

For me, the retro gaming and home computing era began in the late 1970s and early 1980s, marked by the golden age of arcades, the rise of consoles such as the Atari 2600, and the emergence of home computers like the Sinclair ZX Spectrum, Commodore 64, and, a little later, the Amiga. While many would certainly think of the 286, 386, and 486 PCs that followed as having vintage appeal now, I felt that the magic had started to fade a little by that time, even as PC games began to thrive.

SPACE WARS

Living in the UK, where space is at a premium for the majority of people, I count myself lucky to have an arcade or games room of any description.

Perhaps it’s a general lack of free space found in UK homes that explains why home arcades have never really been a thing here, and may never be. For many on these islands, simply accommodating a new espresso machine or toaster presents a huge challenge, so it’s no wonder few arcade cabinets enter UK homes.

In contrast – if YouTube is any indicator – it would appear that the average suburban house in America can accommodate an entire cinema, arcade, bar and bowling complex. Even espresso machines and toasters get their own rooms.

THE MAGIC OF THE GOLDEN ERA

Arcades of the 1980s, as I recall, were an assault on the senses from the moment you entered them, providing not only solo gaming but a social and competitive experience as well. A place to huddle with friends in the warm glow of CRT monitors, eagerly competing on games such as Outrun, Space Invaders, Pac-Man, Defender, Star Wars, Battlezone, Pole Position and countless other era-defining classics.

These glorious establishments have always been more than just a collection of machines — offering immersive experiences that are greater than the sum of their parts. With deceptively simple designs built-into the very fabric of their cabinets — much like Nintendo’s synergistic approach to hardware and game creation — arcade machines were made to function as a cohesive whole: a mesmerising combination of aesthetics, hardware functionality and gameplay mechanics. They were — and continue to be — a celebration of the sensory experience of gaming, and an unforgettable fusion of art, design, and technology.

In an era of games industry saturation and emulation-based machines boasting “thousands of games”, there’s something pretty compelling about the idea of an arcade cabinet that plays just one game properly.

With few menus to negotiate and no compatibility issues to contend with, vintage arcade machines remind me of the relatively uncomplicated, uncluttered pre-internet era of gaming — a time when it felt as though every big new game — or film, for that matter — became an event shared by millions.

During the 1980s in particular, the eye-catching cabinets on offer — with their wonderfully vibrant side art, striking marquees, attract modes and unique control schemes — managed to lure in millions of players in on an epic scale, each and every day of the week.

There are establishments offering a 1980s-style arcade experience in the UK today, thankfully, but they are few and far between. One great one, quite local to me, is Arcade Archive, which can be found just outside Stroud in Gloucestershire. Situated above The Cave – a fantastic, hands-on retro tech museum – both are well worth visiting. Together they form The Retro Collective.

As I play — and revel in the sound of — classics such as Space Invaders and Defender in the studio arcade, I’m reminded of the immediacy and accessibility of the gaming experiences arcades used to offer, and I marvel at their enduring, cross-generational appeal — even now, in the era of photorealistic graphics and VR technology.

The arcade games of old epitomised the very essence of casual gaming: easy to learn, hard to stop playing, difficult to master — serving now not only as a lesson in gaming history and a nostalgic reminder of a bygone era, but also as a refreshing counterpoint to some of today’s more complex and convoluted gaming experiences.

The allure of these games is undoubtedly magnified a little by the realisation that they laid the foundations of an entire industry — an entire art form, even — establishing many of the ground rules and conventions that still hold sway today. Their lasting appeal isn’t only about the games themselves, then, but the cultural impact many have had as well, and the very fact they were the first. – JH